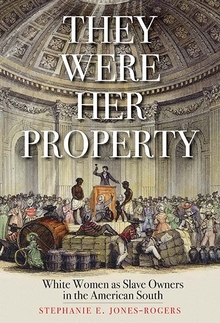

They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, Yale University Press, 320 pages, bibliographic notes, bibliography, illustrations, index, 2019, $30, hardcover.

They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, Yale University Press, 320 pages, bibliographic notes, bibliography, illustrations, index, 2019, $30, hardcover.From the Publisher: Bridging women’s history, the history of the South, and African American history, this book makes a bold argument about the role of white women in American slavery. Historian Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers draws on a variety of sources to show that slave-owning women were sophisticated economic actors who directly engaged in and benefited from the South’s slave market. Because women typically inherited more slaves than land, enslaved people were often their primary source of wealth. Not only did white women often refuse to cede ownership of their slaves to their husbands, they employed management techniques that were as effective and brutal as those used by slave-owning men. White women actively participated in the slave market, profited from it, and used it for economic and social empowerment. By examining the economically entangled lives of enslaved people and slave-owning women, Jones-Rogers presents a narrative that forces us to rethink the economics and social conventions of slaveholding America.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers

is assistant professor of history at the University of California,

Berkeley. She is the winner of the 2013 Lerner-Scott Prize for best

doctoral dissertation in U.S. women’s history. She lives in El Cerrito,

CA.

Christian Century Magazine review by Edward J. Blum (April 18, 2019):

Eva Jones was devastated. The Civil War had left some friends and family members maimed and others dead. Because of economic inflation and stagnation, she could no longer afford some everyday goods. Perhaps most upsetting was emancipation. Before the war, Jones was a member of a prominent southern family and a slave owner. She fumed in a letter to her mother-in-law that the loss of her human property constituted “unprecedented robbery” that would render her “a heap of ruins and ashes.” She lamented the life she would lead when no longer a mistress: a “joyless future of probable ignominy, poverty, and want.”

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers chronicles the financial realities and choices of slave-owning women like Jones, uncovering a world of women’s participation in the institution of slavery that is often undervalued by other scholars. With an array of evidence ranging from court records to newspaper advertisements, ruminations of slave traders to remembrances of former slaves, Jones-Rogers places slaveholding mistresses at the core of slavery’s economy. These women were perceptive players in the buying and selling of men and women. Rather than passive victims of patriarchy and the system of slavery, they were coconspirators in the economic exploitation of people.

Jones-Rogers shows how young mistresses were cultivated to manage and discipline slaves through childhood education. Some of the training came from parents directly. Girls learned other lessons by watching, even by reading a children’s newspaper. The day when a girl first received legal rights to slaves was a noteworthy occasion, as important as a birthday or other holiday.

Dissecting the way women worked within slavery’s financial world, Jones-Rogers finds no discernible differences between mistresses and masters in their treatment of slaves as property. Both women and men exploited enslaved people for their economic benefit. Curiously, however, Jones-Rogers largely omits discussion of the prevalence and economic consequences of sexual contact between masters and slaves—or between mistresses and slaves.

Slave auctions were considered detestable by many, and a

story emerged in the South that women would avoid the tawdry affair of

separating families and friends. Jones-Rogers rips apart this

fabrication. She shows how mistresses were active participants in the

market at every step of the system. They discussed trades within their

homes, brought slaves to traders for sale, circulated around the

auctions to gather information, and purchased and sold slaves.

Slave auctions were considered detestable by many, and a

story emerged in the South that women would avoid the tawdry affair of

separating families and friends. Jones-Rogers rips apart this

fabrication. She shows how mistresses were active participants in the

market at every step of the system. They discussed trades within their

homes, brought slaves to traders for sale, circulated around the

auctions to gather information, and purchased and sold slaves.In perhaps her most interesting chapter, Jones-Rogers looks at the one arena of slave ownership where white women largely created and defined the market: wet nurses. There were many reasons a mistress might want a slave woman to provide nourishment for newborns. One was to free the mistress from the labor of nursing, especially if she was in poor health. Another was to offer sustenance to enslaved babies. Wet nurses became prized commodities, and they were often regarded as skilled laborers.

Overall, the book makes two points clear. First, women acted in their own best interest financially and socially. They followed the prices and values of slaves; they sold and purchased men, women, and children; and they often kept their finances separate from those of their husbands. Second, women’s slave ownership caused considerable conflict between white people. Husbands frequently wanted to control the assets of their wives, and parties often ended up in court over matters of slave control.

They Were Her Property will generate significant conversation among historians of the American South and slavery. While it includes ample qualitative evidence (petitions, court cases, recollections, and other textual documents), economic historians may complain that it lacks the quantitative data that would demonstrate mistresses’ monetary impact and their power to generate broader social change. Jones-Rogers presents legal and political history, but she rarely includes macro-statistics to place slave-owning women within broad trends and developments.

In the 1930s, workers for the Federal Writers Project—a New Deal organization dedicated to combating unemployment during the Great Depression—interviewed former slaves about their experiences. Jones-Rogers relies significantly upon these interviews, although some historians wonder if they are more useful for understanding race relations in the early 20th century than slavery in the 19th. Since slavery had ended 65 years earlier, many of the interviewees had been children at the time of emancipation. There are also concerns that the interviews are shaped by the influence of white interviewers. Whether the interviews are suitable for the study of slavery, Jones-Rogers puts them to excellent work. She shows that the interviewees understood white women to be part of, rather than subject to, the economic realities of enslavement.

Amid the vignettes of slave-owning women using their power and authority, Jones-Rogers frequently chastises other historians for failing to present southern white women as active players in slavery. The point is important, but it becomes tedious to read repeatedly. If readers simply skip those paragraphs, they will find a gripping story of female businesswomen using their property—in this case, human beings—to make money. These women were not pawns in the racialized nation we still inhabit; they were players.

Full text link to Christian Century review: Christian Century April 18, 2019

Author's Photograph Source

Yale University Press Source They Were Her Property

No comments:

Post a Comment