Brown's Island Munitions Explosion Was Worst Wartime Disaster In Richmond, Katherine Calos, Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 4, 2017

The first blast lifted Mary Ryan off the floor. The second blew her to the ceiling. The Confederate munitions factory on Brown's Island exploded with a fury that killed more than 40 of its female workers, an event that shocked the city on March 13, 1863, and inspired an outpouring of sympathy.

The homefront disaster was Richmond's worst during the Civil War. Its 150th anniversary was commemorated with living history programs at The American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar and with the dedication of a historical marker beside the island.

Ryan, an Irish teenager like many of the other workers at the Confederate States Laboratory, accepted blame for the explosion during the several days she lingered in pain. She confessed to Col. Josiah Gorgas, chief of ordinance, that she had banged a perforated wooden board containing friction primers against a table to knock them loose. The jostling was strong enough to ignite at least one of the primers, which set off an explosion that demolished most of the 70-foot building.

Between 80 and 100 workers, mostly women, were in the room either at their jobs or warming themselves at a coal stove. An official report counted 69 casualties, of whom at least 44 died. "The most heart rending lamentations and cries issued from the ruins from the sufferers rendered delirious from suffering and terror," the Richmond Examiner wrote of the scene in its March 14 edition. "No sooner was one helpless, unrecognizable mass of humanity cared for and removed before the piteous appeals of another would invoke the energy of the rescuers."

Only a few of the victims died

instantly. Others suffered "the most horrible agonies, blind from burns,

with the hair burned from their heads, and the clothing hanging in

burning shreds," the Examiner wrote. A few jumped in the river to

extinguish the flames. For the rest of the month, deaths

from the accident mounted. Mary Ryan, age 18, died March 16 at the home

of her father, Michael Ryan, who also worked at the arsenal.

Elizabeth Young, 25, died in a

rented room on Oregon Hill "after a severe pain of twelve hours, caused

by the fearful accident on Brown's Island," the Daily Dispatch reported

March 17. "This will be sad news to her relations and friends, whom she

left not long since in Caroline county."

Only three of the dead were men.

The Rev. John H. Woodcock, 63, was supervisor of the room where the

blast occurred. James Curry, 13, died the night of the explosion from

his injuries. Samuel Chappell, 16, somehow lived five days after being

found wedged against a wall with his skull crushed from the collapse of

the building's roof.

In an official inquiry by the War

Department, Capt. Wesley N. Smith, superintendent, estimated that the

room that exploded had contained 200,000 musket caps, 2,000 to 3,000

friction primers and about 10 or 11 pounds of gunpowder. It was more crowded than normal because materials weren't available to finish an expansion of another building. The mixture of jobs increased the

risk of an accident. In addition to finishing friction primers, sewing

cannon cartridge bags and boxing musket caps, workers were filling

Williams cartridges and taking apart defective cartridges to separate

the gunpowder and lead. As a result, gunpowder dust would've been in the

air.

Friction primers were a detonation

device for cannons. When the cannoneer pulled a lanyard attached to the

friction primer pin, the effect was the same as striking a match. The

spark ignited gunpowder inside the metal primer tube, and that small

explosion ignited a larger charge inside the cannon.

As a last step in the

manufacturing process, the primers were sealed with wax and varnished to

protect against moisture, which possibly caused some of them to stick

to the board that held them for manufacturing.

Many of the munitions workers were

young women because their small, nimble fingers were considered more

suited to the task of assembling up to 1,200 cartridges a day. Cathy Wright, curator at the

Museum of the Confederacy, sees a parallel to Rosie the Riveter in World

War II in the way women were sought for jobs that previously would have

been off-limits. Before the Civil War, Wright said,

"women had not been encouraged to find gainful employment. They were

supposed to stay at home. Working for wages was a couple of steps above

being a lady of the night."

The explosion made it harder to accept

the idea of women in workplace, Wright said, but it didn't stop women

from working. The community responded with contributions of $9,000 to

$10,000 for the victims. The munitions lab on Brown's

Island didn't exist until after the war began. Smaller explosions at its

original location at the end of Seventh Street had raised safety

concerns. So, the island was cleared and a group of one-story wooden

buildings was constructed for the operation in 1863.

Explosions were an occupational

hazard in munitions manufacturing, said Dean S. Thomas of Gettysburg,

Pa., author of Round Ball to Rimfire: A History of Civil War Small Arms

Ammunition.

On the same day as the battle of

Antietam in September 1862, an explosion at the Allegheny Arsenal in

Pittsburgh had killed 78 workers. An arsenal explosion in Jackson,

Miss., had killed about 40 people a few weeks later. "When they

advertised for people to make cartridges," Thomas said, "they would

advertise that it was as safe as anything else."

Text Source: Richmond Times Dispatch

Slight modifications in the text related to current events' dates have been made in this post.

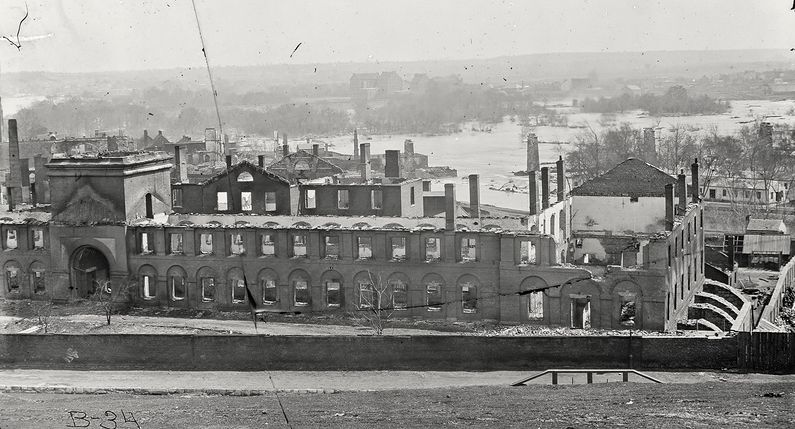

Image Source: Richmond Arsenal

Text Source: Richmond Times Dispatch

Slight modifications in the text related to current events' dates have been made in this post.

Image Source: Richmond Arsenal