A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide To the Union and Confederate Hospitals at Gettysburg, June 1-November 20, 1863, Gregory Coco, Savas Beatie Publishing, Paperback, 224pages, profusely illustrated, maps, appendices, index, bibliographic endnotes, $19.95 On Sale: January 15, 2018

A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide To the Union and Confederate Hospitals at Gettysburg, June 1-November 20, 1863, Gregory Coco, Savas Beatie Publishing, Paperback, 224pages, profusely illustrated, maps, appendices, index, bibliographic endnotes, $19.95 On Sale: January 15, 2018

Nearly 26,000 men were wounded in the three-day battle

of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863). It didn't matter if the soldier wore

blue or gray or was an officer or enlisted man, for bullets, shell

fragments, bayonets, and swords made no class or sectional distinction.

Almost 21,000 of the wounded were left behind by the two armies in and

around the small town of 2,400 civilians.

Most ended up being treated in

makeshift medical facilities overwhelmed by the flood of injured. Many

of these and their valiant efforts are covered in Greg Coco's A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide to the Union and Confederate Field Hospitals at Gettysburg, July 1-November 20, 1863.

The battle to save the wounded was nearly as terrible

as the battle that placed them in such a perilous position. Once the

fighting ended, the maimed and suffering warriors could be found in

churches, public buildings, private homes, farmhouses, barns, and

outbuildings.

Thousands more, unreachable or unable to be moved remained

in the open, subject to the uncertain whims of the July elements. As

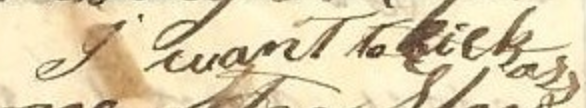

one surgeon unhappily recalled, "No written nor expressed language could

ever picture the field of Gettysburg! Blood! blood! And tattered flesh!

Shattered bones and mangled forms almost without the semblance of human

beings!"

Based upon years of firsthand research, Coco's A Vast Sea of Misery

introduces readers to 160 of those frightful places called field

hospitals. It is a sad journey you will never forget, and you won't feel

quite the same about Gettysburg once you finish reading.

CWL: The first published in 1988 by Thomas Publications [Gettysburg, Pennsylvania], A Vast Sea of Misery is 30 years old. Coco's work on this and related fields began something new. Firm in in his scholarship and relying upon soldiers' recollections and letters, Coco then integrated farmers' damage claims to both the Federal and Pennsylvania governments into the Battle of Gettysburg narrative. A Vast Sea of Misery also opened up the study of the borough and its civilians, religion and the volunteerism which occurred after the battle. CWL has two copies, one hardback and paperback; the former near mint the latter thoroughly marked with notes. Savas Beatie is congratulated for keeping A Vast Sea of Misery in print.