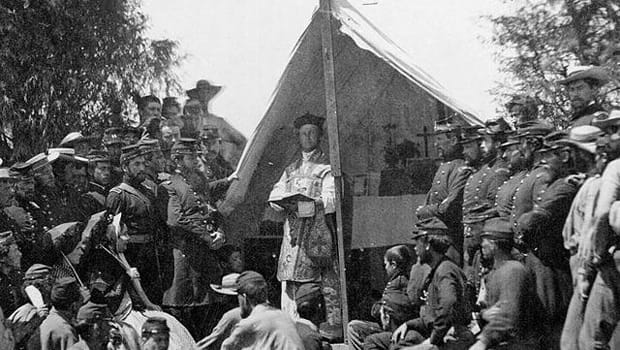

Civil War Photographs--Four Nearly Identical Images 'Move' With the Help of Software

Matt Loughrey, the founder of My Colorful Past, lives on the west coast of Ireland. His work exists somewhere between history and art, using technology as the storyteller. Above, you can watch his latest project. Below, Elisabeth Pearson interviews him about the value of his work.

1. Were you always interested in combining art and history? How did your interest in reanimation begin?

Digital art has always been in the background for me. My first experience of that was in 1991 and getting myself accustomed to Dan Silva's 'Deluxe Paint' software on the Commodore Amiga. It was a very defining time in light of my own creativity. Almost three decades later, art software is still as groundbreaking and archives of historical material are accessible through the internet, not least the ability to communicate freely with archivists the world over. It always made sense to combine both interests.

2. Has living in Ireland influenced your work? If so, how?

In the west of Ireland there's a very real sense of creative community. Creativity is widely accepted and fostered by those that appreciate it. I think that overall acceptance and the peaceful surrounds of home are positive for work.

3. How did you discover that these frames could be inadvertently reanimated?

I've spent many years stumbling upon what I thought could be duplicate frames that were uncatalogued in different archives. For the most part I dismissed them, until it became more and more obvious to me that it might be worthwhile looking at closely. I looked at a couple closely and it was like finding treasure in plain sight.

4. Your Instagram, My Colorful Past, has taken on quite a following. How do you manage that account? Are you pressured to come up with new content? What are some of your favorite images you’ve posted?

People with specific interests look for quality content, provided I keep that in mind then the account becomes somewhat self managing. It's hard to say what is a favorite image, albeit I've always enjoyed American history as it has been so very visually documented, it makes the experience relatable almost. The Gold Rush, The Dustbowl, The Civil War, Ellis Island...

5. What do you hope your viewers get out of the documentary and or the work that you do?

The aim is always to invite a completely new sense of relatability and the opportunity to learn a little more.

6. How has this project changed or developed since you first started back in July 2018?

The project itself has been realized, in this instance that was was the main priority. So long as it exampled what is possible then I was going to be happy with the outcome. The interesting part on a professional level are the expressions of interest from libraries and museums that see its potential as an aid to their visitor experiences.

7. Do you remember the first time you saw the reanimation of an image? Which image was it and did it provoke any feelings that may have inspired this mini documentary?

The first portrait I animated authentically was of George Custer when he was a Captain. In that moment he was 'alive' and I fast realized the potential as well as importance of seeing the project through. It was very surreal in the sense of discovery, that I do remember well.

8. What do you hope to accomplish moving forward with the reanimation of frames?

The integral part of this project is realizing that it is all about preservation and discovery combined. The end goal is to see these animations, and hundreds of others, displayed in the correct learning environment. They are ideal as an engaging visual support for classroom learning in the digital age. What better, than to see in motion, the very people or places you are reading about.

Text and Video Source: History News Network