Army University Press: The ‘Union Army’ Is No More, By Fred Bauer, National Review, April 27, 2021

Having triumphed over rebel forces 160 years ago, the Union army now faces a new challenge: the effort to erase it from history books The Army University Press announced new guidelines for article and book submissions that strongly discourage the use of the term 'the Union' to refer to the forces of the U.S. government during the Civil War.

Similarly, citizens in states who remained loyal to the

United States did not all feel a strong commitment towards dissolving

the institution of slavery, nor did they believe Lincoln’s views

represented their own.

Thus, while the historiography has traditionally

referred to the “Union” in the American Civil War as “the northern

states loyal to the United States government,” the fact is that the term

“Union” always referred to all the states together, which clearly was

not the situation at all. In light of this, the reader will discover

that the word “Union” will be largely replaced by the more historically

accurate “Federal Government” or “U.S. Government.” “Union forces” or

“Union army” will largely be replaced by the terms “U.S. Army,”

“Federals,” or “Federal Army.

However, it’s not just “the historiography” in the abstract that has

referred to the states loyal to the federal government as “the Union.”

The people who fought to preserve the Constitutional order called their

side “the Union,” too. In his memoirs, Ulysses S. Grant referred many

times to the “Union army” or “Union troops.” Countless documents written

during the Civil War (by those who fought against the Confederacy)

spoke of the “Union army.” Referring to the effort to preserve the U.S.

federal government during the Civil War as “the Union” is not some

retrospective invention of historians.

In fact, it’s arguable that erasing the term “the Union” from

historiographical discourse, far from being “more historically

accurate,” distorts the vision of Lincoln, Grant, and many other

Americans.

“Union” has a particular charge in American discourse, from the

Constitution’s “more perfect Union” onward. In his first inaugural

address, Lincoln reflected on the centrality of the hopes of union for

the American republic. He held in that address that secession was not

just the splintering of the United States but the obliteration of

political order: “The central idea of secession is the essence of

anarchy.” The secession crisis threatened the U.S. government, but

Lincoln and his contemporaries also saw violent secession as threatening

the prospect of democratic governance in general.

The project of Union was about the U.S. federal government, but it

was about more than that, too. Union was the hope of reconciling

conflict within a democracy. Union was the assertion of the rule of law

over factional violence. Union was securing the prospect of republican

liberty. For many Americans, the army that marched under the Stars and

Stripes was in that deeper sense the Union army.

In his funeral sermon for Abraham Lincoln, the minister Phineas

Gurley did not once mention the “federal government” or even “United

States.” Instead, he spoke again and again about “union”: “through all

these long and weary years of civil strife, while our friends and

brothers on so many ensanguined fields were falling and dying for the

cause of Liberty and Union.” If one of the goals of historical study is

to capture the textures of past eras, erasing “the Union” and “the Union

army” from historical discourse would make it harder to understand the

passions and principles of those who risked their lives to preserve the

American republic.

Image: accompanying National Review online article

Union troops form near the battlefield during a re-enactment of “The

Wheatfield” as part of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg

in Gettysburg, Pa., July 5, 2013. (Gary Cameron/Reuters)

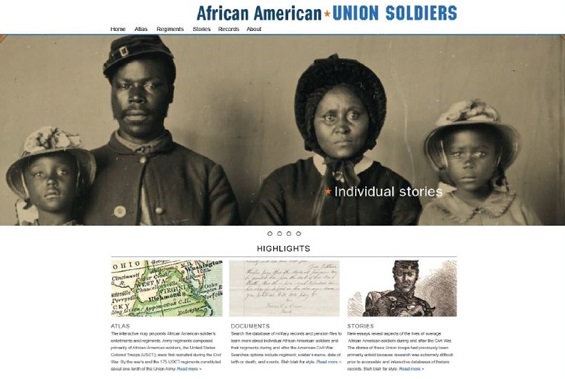

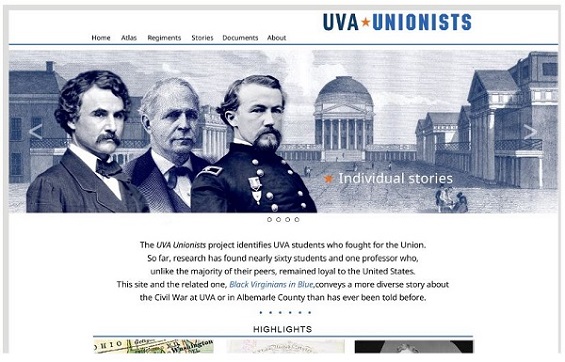

UVA Unionists: Digital Project Studying University of Virginia Alumni Who Stayed Loyal to the Union

UVA Unionists: Digital Project Studying University of Virginia Alumni Who Stayed Loyal to the Union